Here is a perfect craft cocktail that is cooling and refreshing for these late summer, fresh mint-filled days. If you are into Mint Juleps this version really heightens the mint flavor in a satisfying way.

Mint Bourbon–Julep Wild Style

Makes 16 oz, serves 4–6

This lightly sweetened liqueur captures the essence of fresh mint. To achieve good flavor, purée the plants, then steep the mixture for a bit of time. Serve at social gatherings, or pour them into attractive bottles and give them away as gifts. The alcohol content of this drink ranges from 25% when using 80 proof to 31% when using 100 proof.

• 10 oz 80–100 proof bourbon

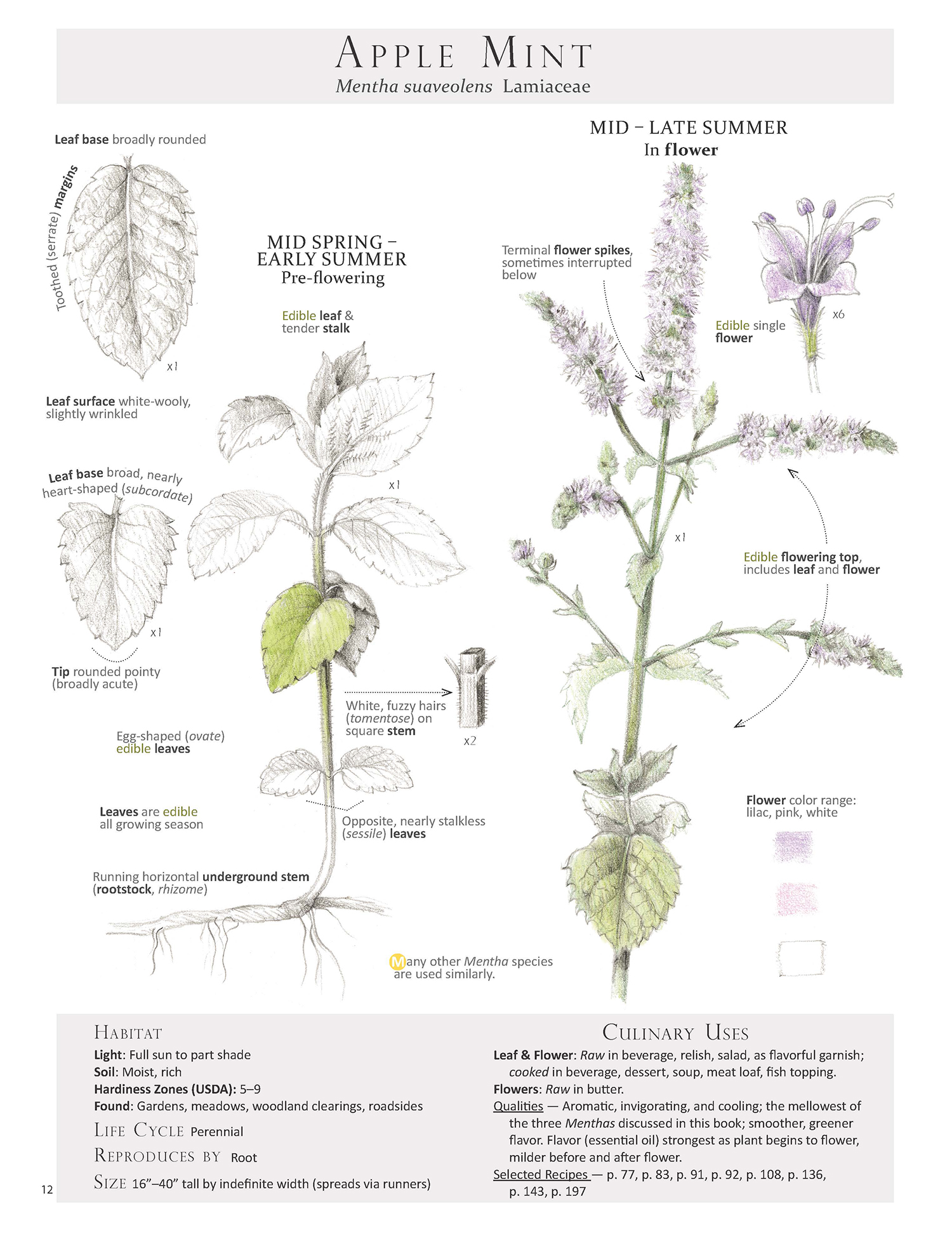

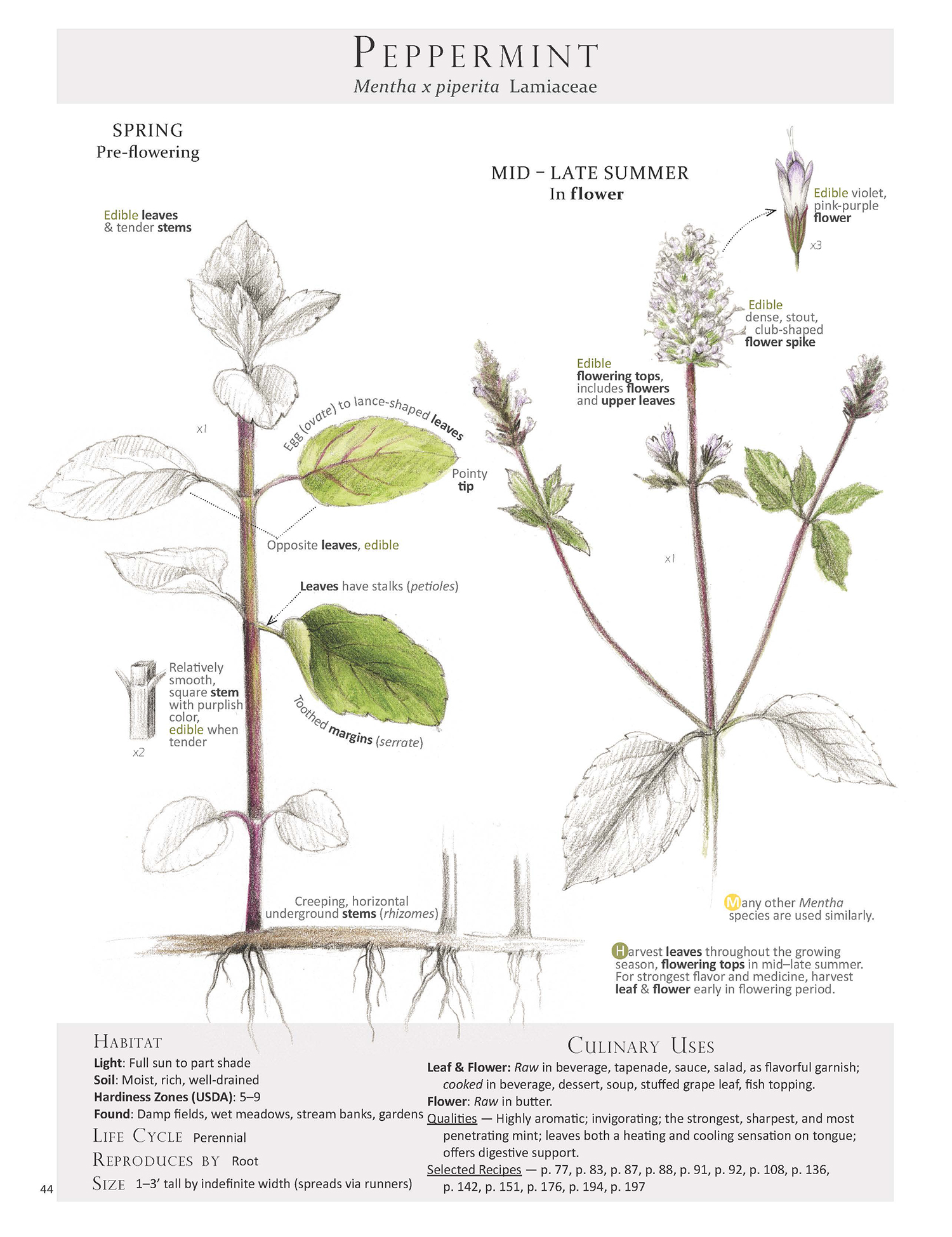

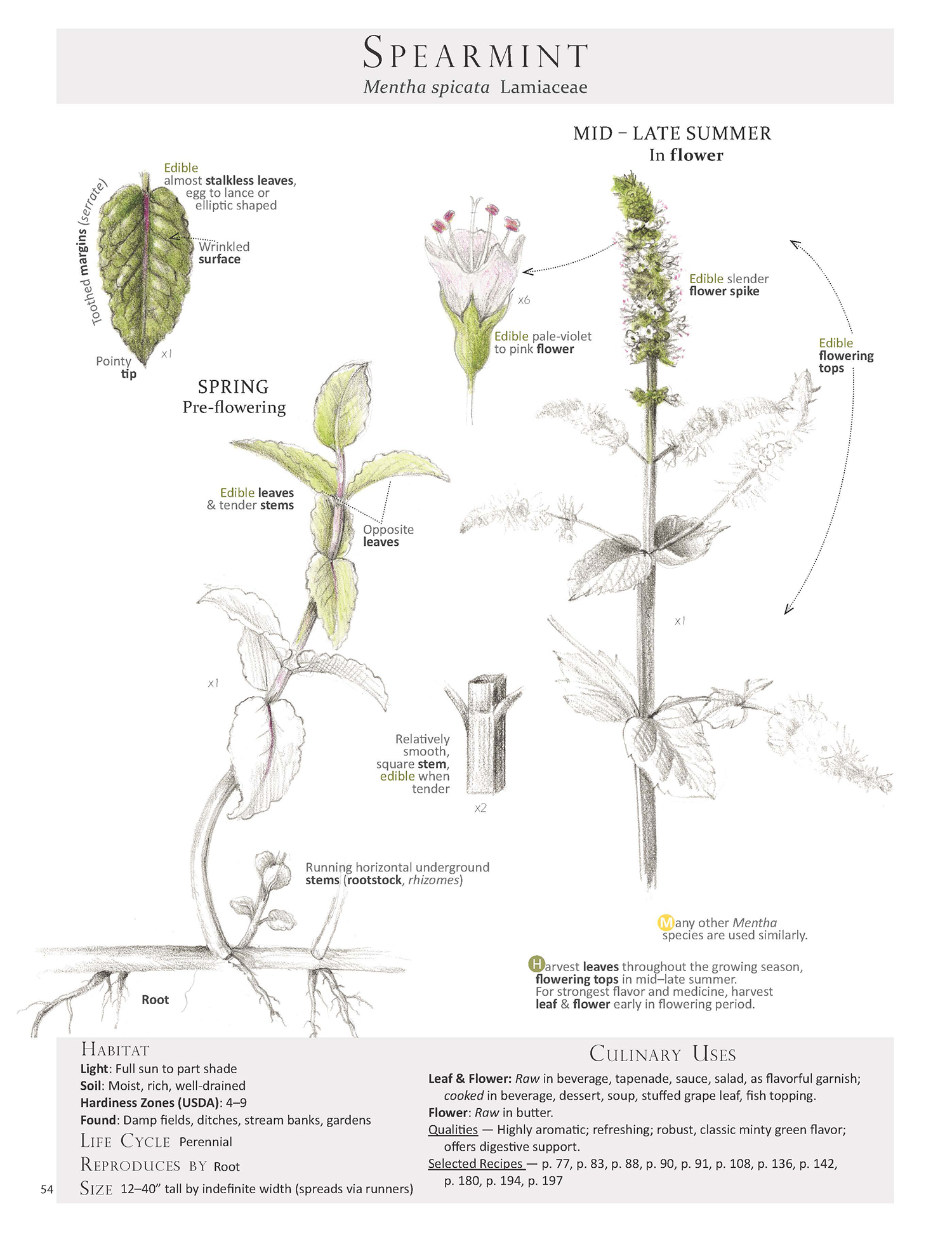

• 2 large handfuls fresh leaves or flowering tops of apple mint, peppermint, and spearmint (stripped off main stalk). I like this mint combo, but if you only have one kind of mint, by all means use it.

• 4 oz water

• 3–4 tablespoons maple syrup

Purée ingredients in a blender, pour into a glass jar, cover with a tight-fitting lid and leave out for about an hour, or for up to four weeks at room temperature. Strain through a fine-mesh sieve, and squeeze the plant material to remove as much liquid as possible. If you would like to remove all plant particles, line the sieve with a thin linen cloth before straining. Serve over crushed ice and garnish each glass with a fresh mint leaf, if available. To store, pour into a glass bottle, cap tightly and keep in a cool, dark place. This Mint Bourbon keeps for at least a year, and although it won’t rot due to the alcohol content, the aromatic flavors decrease with time.

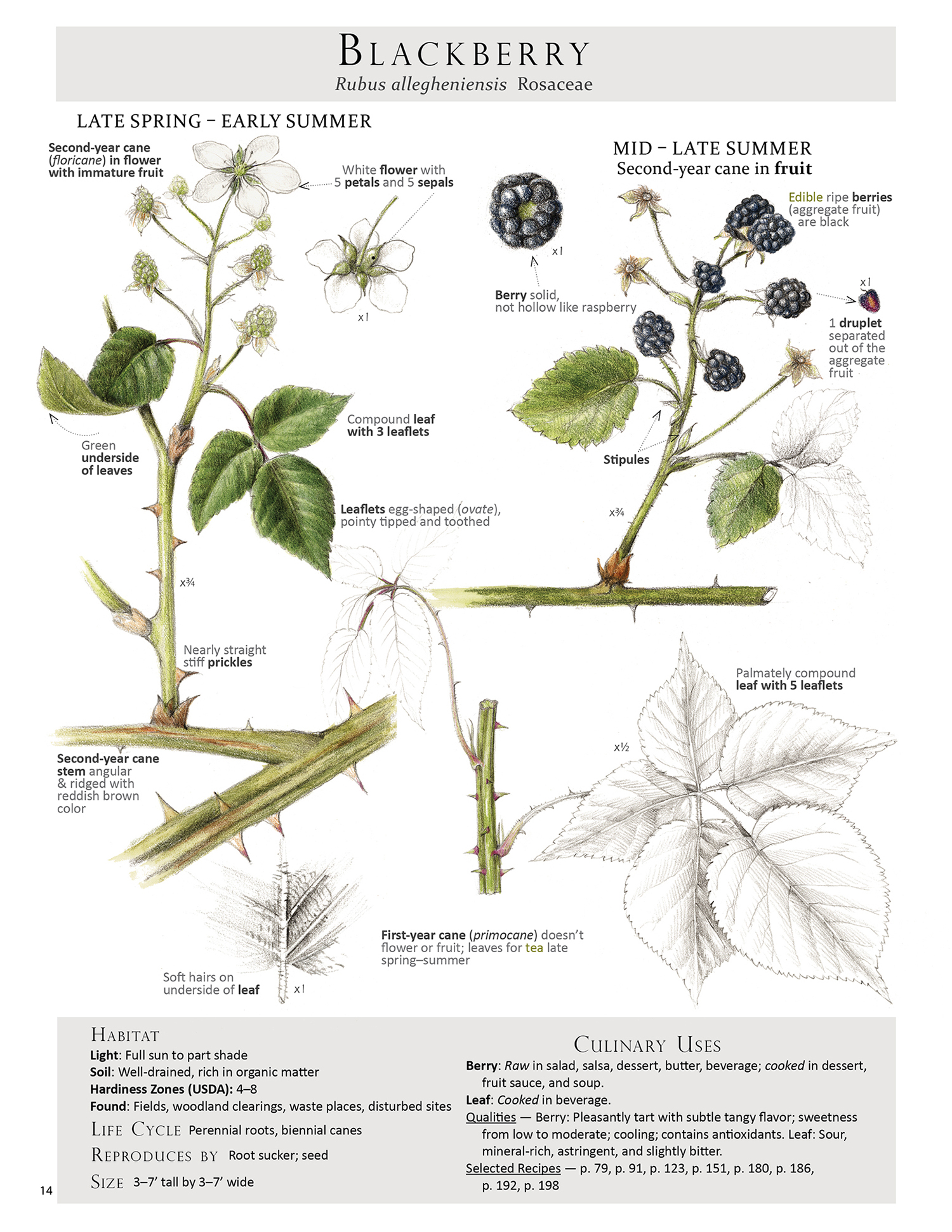

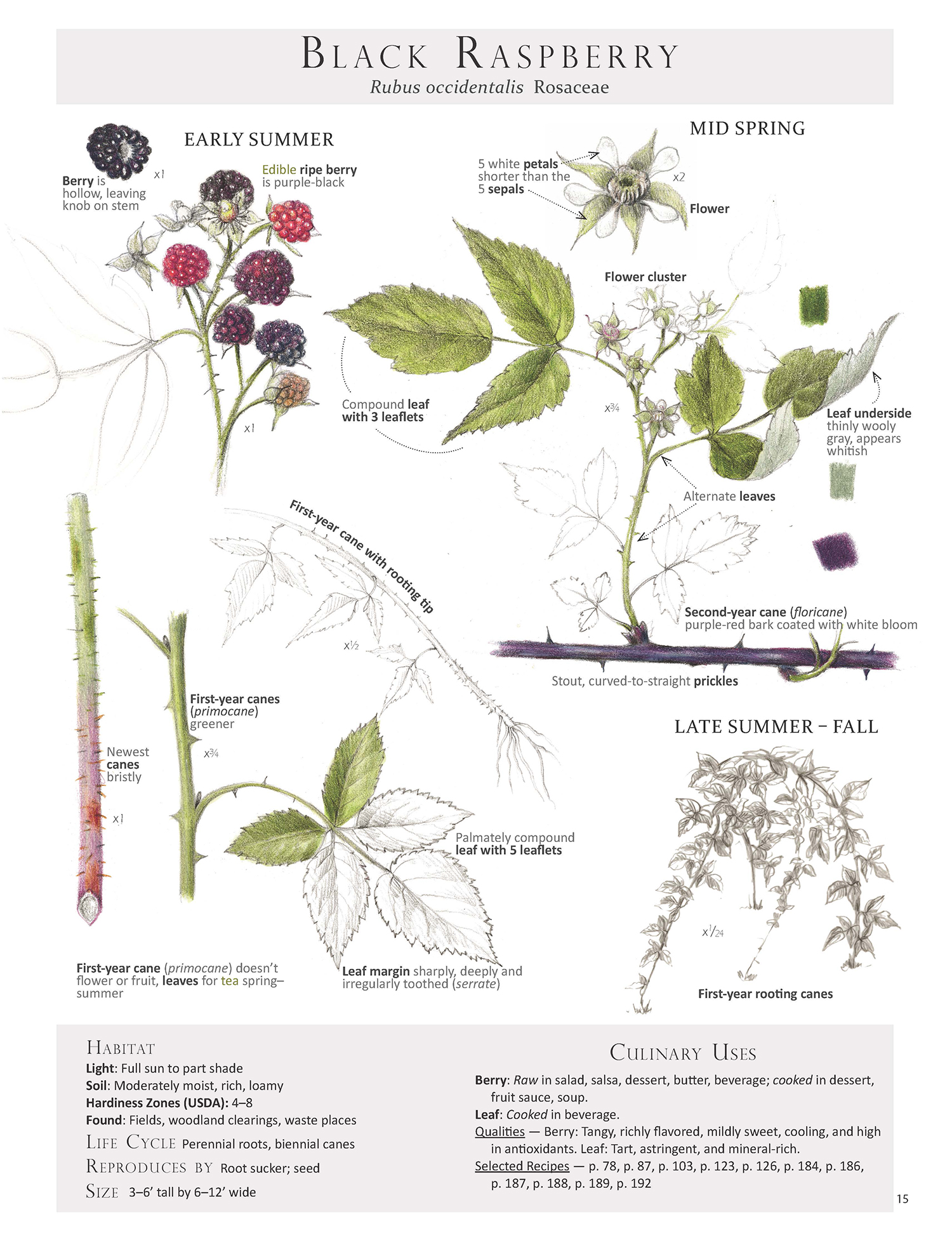

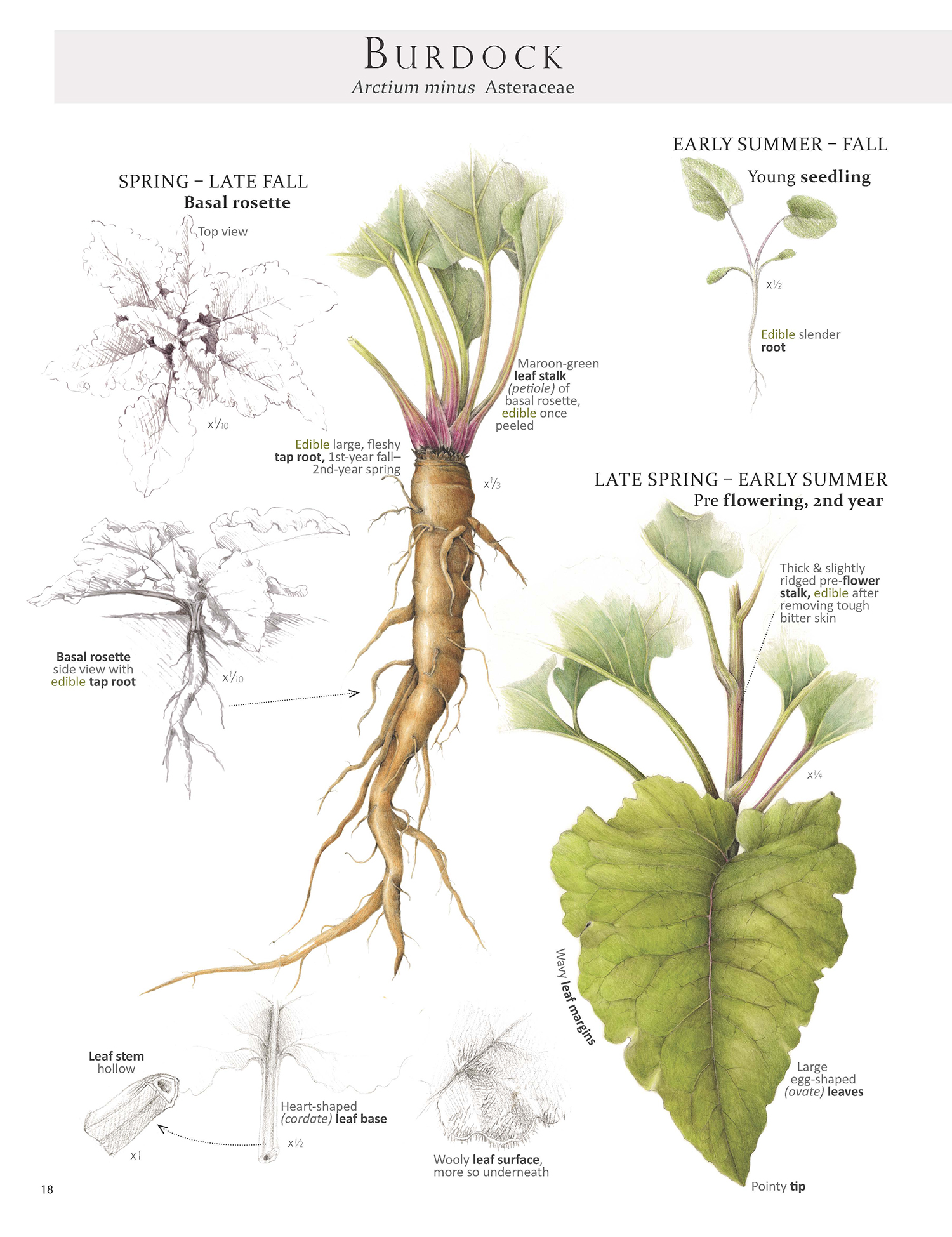

Recipe excerpt and mint identification pages from our Foraging & Feasting: A Field Guide and Wild Food Cookbook by (me) Dina Falconi; illustrated by Wendy Hollender. Book link: http://bit.ly/1Auh44Q